Particle Physics

I once helped build particle detectors

It all began on the London Underground in 2015 when I saw one of my professors, Henrqiue Araujo, on the train. We spoke about his research on dark matter, and he offered me to work in his group over the summer.

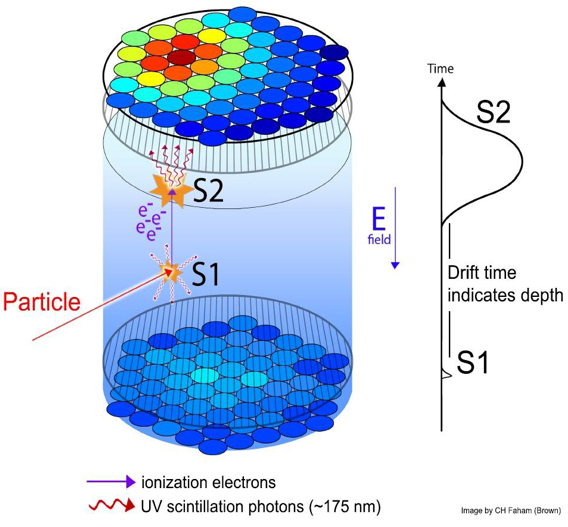

Dark matter is the elusive substance that is theorised to comprise 85% of the mass in the universe. The search for dark matter is about to reach new heights with the start of the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment. The discovery of dark matter would cause an almighty revolution in physics, most notably the Standard Model of particle physics would be overthrown and it is likely that a plethora of new science would be generated as a result. LZ makes use of a time-projection chamber, filled with Xenon. Dark matter interacts with Xenon nuclei to produce light, which is then amplified and detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT). However, cathodic surfaces in the detector are known to emit spurious photon and electron, which could potneitally lead to a false detection of dark matter. My job was to simulate the detector to understand it’s electric field, and photon detection efficiency. In order to perform the simulations I was exposed to new software, including a C++ based toolkit named Geant4. This toolkit employs Monte Carlo methods to simulate high energy particle experiments, including those at CERN. Using these simulations we were able to understand and control for this effect, as described in our publication.

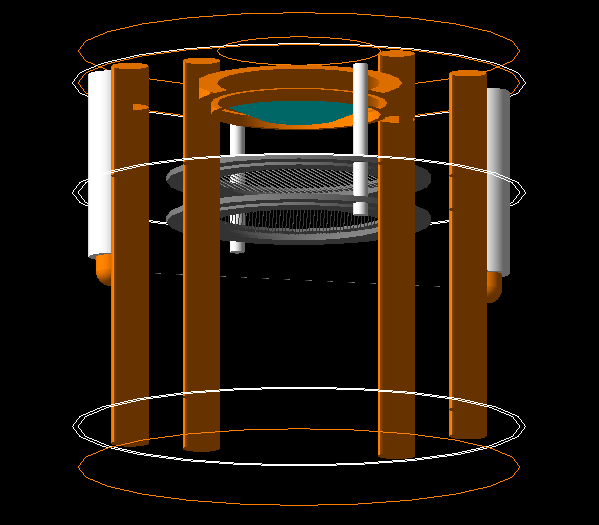

The next summer, I was given the oppurunity to work in the Laboratory for Nuclear Science at MIT under the supervision of Professor Lindley Winslow. She and her team are planning on building a prototype neutrinoless double beta decay detector, named NuDot, which will make use of quantum dot technology and Cherenkov radiation to drastically reduce the background in experimental data and in turn make any signal of discovery much more noticeable.

Neutrinoless double beta decay is a very rare theoretical nuclear interaction in which two neutrons simultaneously convert into two protons and two electrons, without the production of any neutrinos. If found to occur it would imply that neutrinos are their own antiparticle and lepton number is not conserved. One modern technique of searching for this interaction is by use of a scintillator. Scintillators produce light as they interact with charged particles and so can be used to detect the electrons produced in the decay. However, this scintillation light is isotropic at the energy of operation and so does not contain information regarding the electrons’ trajectories.

But all is not lost, as another type of radiation, known as Cherenkov radiation, occurs when a particle travels through a medium faster than light. Cherenkov radiation is emitted in a specific direction depending only on the refractive index of the medium and the velocity of the particle. If this Cherenkov radiation were to be detectable, without being lost amongst the scintillation radiation, scientists would be able to use the directional information to help determine whether or not an interaction was indeed neutrinoless double beta decay. In order to achieve this the scintillator is doped with quantum dots, enabling control of the emission spectrum and thus separation of Cherenkov and scintillation radiation. For proof of concept, MIT have built a prototype of NuDot capable of performing the above.

My research concerned producing simulations of the goings on inside the detector, working out what we would expect to see when performing actual experiments. We were able to determine the most ideal configuration for the experiment. After this, we brought my simulations to life by setting up multiple thousands of dollars worth of photomultiplier tubes (PMTs).